Thank God It's Monday: How Management Weaponised the Idea of Happiness at Work.

In 1963 The State Mutual Life Assurance Company faced a crippling issue of identity. The firm had recently gone through a turbulent series of corporate mergers, restructurings and lay-offs. Wanting to tackle the understandably low morale amongst the workforce, management launched a ‘smile campaign’ and commissioned the visuals to Harvey Ball, a local graphic artist. That’s the somewhat disappointing genesis of a countercultural icon – the Smiley. Nearly sixty years later, the violence of positivity continues to crumple workers’ souls through clichéd motivational slogans, forced sociability and mandatory fun. Is there an exit? One may say that you always have a choice – you don’t have to work at all or choose a field less dominated by the corporate happiness agenda. But the option is illusionary. If you think you can escape from yuppie optimism to other, neverending-smile-free areas, the choice is limited. From design to marketing, from customer service to the cleaning industry – performative positivity is no longer a personal trait. It’s a requirement.

The Economics of Employee Happiness

The domination of messages about engagement and positivity at the workplace is driven not only by the assumption that happier workers are more productive, but also by the fear of severe economic consequences resulting from employees being mentally withdrawn from their jobs (Davies, 2016). Lack of engagement, along with low-key mental health issues, is believed to be a major factor causing absenteeism or worse, what’s termed in business literature, presenteeism. This widely publicised issue has opened the way to a multibillion-dollar happiness industrial complex, represented by a myriad of positive psychologists, coaches, self-help Gurus and happiness evangelists (Davies, 2016).

The most significant paradigm shift in the field of happiness science and positive psychology has been not the discrediting of Abraham Maslov’s pyramid of needs, but, as Eva Illouz claims in Manufacturing Happy Citizens – its inversion. Traditionally since its conceptualisation in the 1940s and popularisation in 1950s, the common sense and agreement in organisational studies that in order to achieve “higher” needs, “basic” needs, such as safety have to be completed first. Thus organisational science and HR departments would have been focused mostly on researching and improving different work arrangements, environments or job design. However, according to Illouz, in the last decade there has been an assumption shift where leading Positive Psychologists and Happiness Scientists have been promoting the view that happiness is not only the derivative from fulfilling work, success and optimal working conditions but a substantial predecessor of professional achievement (Illouz & Cabanas, 2019).

This assumption has been strongly adopted in the corporate world; trying to heighten the levels of positivity and engagement are seen as an essential strategy to increase productivity. A Chief Happiness Officer at Google, funsultants and so on are only a few amongst roles recently created within the corporate realm. Although the direct correlation between happiness and productivity is disputable, many corporates are adopting measures like happiness or engagement as performance indicators for evaluating projects. Tony Hsieh – one of the most prominent evangelists of this movement and the founder of Zappos – has even suggested companies identify the 10% of employees who are reluctant or critical to these ideas and fire them (Davies, 2016). Jeff Bezos, who is very inspired by Hsieh and happened to buy his company has adopted this strategy too by offering, to employees dissatisfied with the company’s policies and work arrangements, a one-off payment to quit (Umoh, 2018).

Happiness – a Moral Fantasy

The word happy is typically used in one of two ways – as a valuing statement or to describe a psychological state. Understood as the latter its definition is more straightforward – an upbeat emotional state. When used as a valuing statement, happiness correlates with subjective understandings of The Good Life (Haybron, 2020).

Therefore the perception of the good life is a fluid concept, changing throughout time. Some examples of this would be the Aristotelian concept of Eudaimonia – a belief that happiness is derived from living within virtue. It is something that can be only experienced at the end of life. Going further there is the medieval Christian understanding that happiness is reached only in Heaven – the concept of leading a good life was subservient to the art of a good death – ars bene moriendi. Therefore, it is a reward for living a life according to religious rules. It is only until the Enlightenment era that happiness is treated with importance, as a means in its end not as a derivative. Some proof of this intellectual shift is the United States Declaration of Independence and the right to pursue happiness. Enlightenment thought laid the foundations for the individualistic perceptions of happiness in the developed West, even though prudential values were still considered important elements supporting the moral fantasy of happiness. It was not until the counterculture era of the 1960s when the current hyper-individualistic fantasy building on Willhelm Reich’s legacy started to become a norm promoted by enlightened tech entrepreneurs, founding fathers of positive psychology connected to influential institutions such as the Esalen Institute. This moral fantasy of happiness goes something like this: be authentic; enjoy yourself; be productive; don’t rely on others in achieving these goals; your fate is in your hands (Cederström, 2019). This set of values requires constantly exercising self-control in order to optimise our pleasures.

Representations of labour

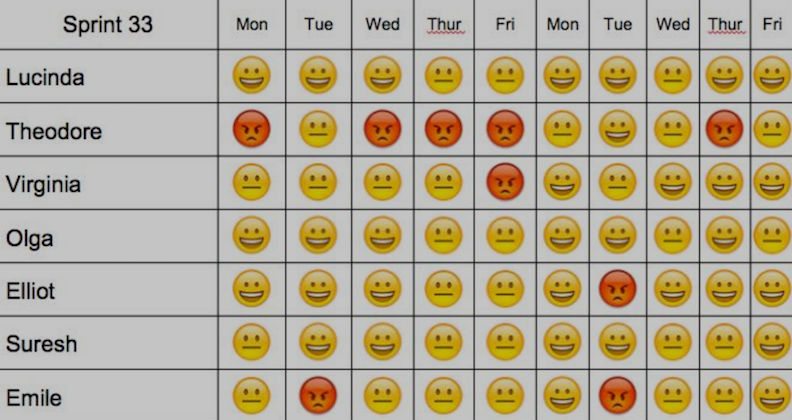

Although happiness understood as a moral fantasy is vague, fluid, and by its nature resistant to quantification, following Drucker’s maxim What can’t be quantified can’t be managed, many businesses turn towards technology and management consultancies for help – giving way to numerous start-ups, agencies and funsultants claiming to have created tools and methodologies that capture and optimise employees’ so-called well-being; but what is important to say that, as with any collected data, it is only the representations of these states.

The whole complexity behind the abstract idea of happiness is simplified and boiled down to single common denominators. What describes these denominators is an ideology that assumes that happiness is something to be developed and optimised. In cognitive capitalism, where the output of labour is often abstract and non-quantifiable, according to Mark Fisher (2009), “What we have is not a direct comparison of workers’ performance or output, but a comparison between the audited representation of that performance and output.” (p. 48) Due to its presumed correlation with productivity, happiness or engagement are often treated as these representations. The production of these representations becomes the main goal, replacing the primary objectives of work, reducing employment to an aesthetic performance (Fisher, 2009). It is no longer about how hard you work – it is about how enthusiastic and vocal you are about it.

Guilt as control mechanism

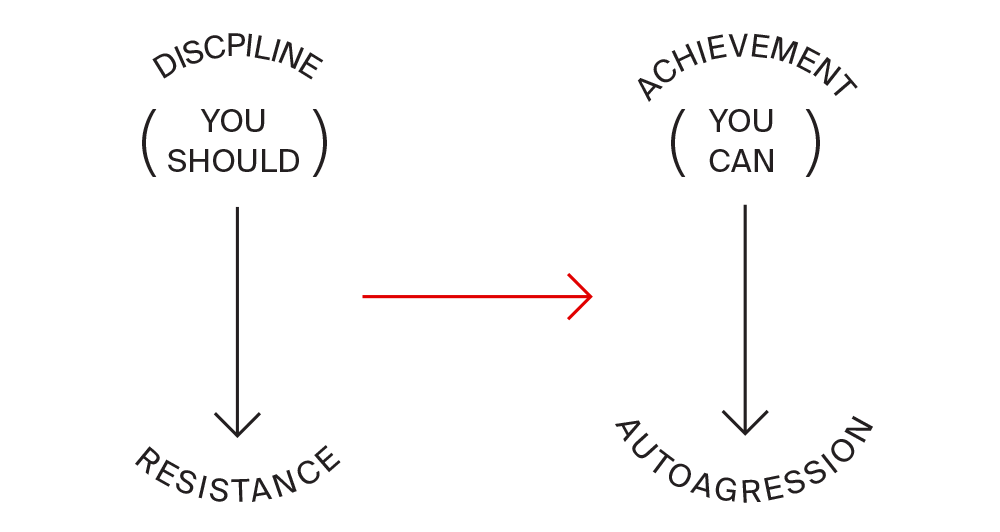

Byung-Chul Han argues that the Foucaldian conceptual model of Biopolitics evolved when shifting from the Disciplinary Society characteristic of Industrial Capitalism toward the Achievement Society characteristic of Cognitive Capitalism Governed by Psychopolitics (Han, 2017).

Labour Process Theory points out the antagonistic relation between the exploiting Capital and exploited Labour. Capital always seeks to maximise the extraction of Labour Power by subjecting workers to discipline. However, the negativity of discipline as a means of increasing economic productivity hits a threshold beyond which it stagnates further growth, by provoking an immune reaction towards Capital in the form of resistance such as Organised Labour (Edwards, 1985).

According to Byung-Chul Han (2017), “Psychopolitics shifts the inefficient paradigm of disciplination towards the efficient, positive paradigm of achievement. Thus, inhabitants of overdeveloped western prosperity are no longer ‘obedience subjects’ but ‘achievement subjects’ ”. The worker becomes an Entrepreneur – an Entrepreneur of Himself. The antagonistic relation between Capital and Labour is blurred. Excessive extraction of Labour Power that would previously result in resistance becomes internalised in different forms of auto-aggression – most commonly guilt (Han, 2017). Because of the dominating ideology that you make your own fortune, you can only blame yourself for any shortage. In these precarious conditions, workers are required to constantly prove to themselves and their employers that they deserve their jobs. In the Achievement Society, enough is no longer enough (Han, 2015). The psychological contract at the modern workplace dictates that one should do more than is required or at least appear to be doing so. The more bullshit a job is, the more the performative aspect is important.

Guilt becomes an important tool of control in the modern workplace and together with anxiety, which often accompanies it, can be caused by numerous factors. The soft but imminent pressure to do more than required causes guilt when you do not match up to the perceived standards of being constantly energetic and ambitious; when you do not push yourself to the limits and step out from your comfort zones on a daily basis (Fisher, 2009). The emotional labour due to the neverending performance of being happy and engaged is more exhausting than the responsibilities listed in a worker’s contract. The spiritual violence of this crying game is an even bigger burden when a worker earns a decent salary for this fruitless but aesthetic performance. The sense of guilt caused by earning a decent (or greater) salary in a Bullshit Job position has become even stronger during the current COVID pandemic, when compared to the situation of underpaid key workers.

Emancipation?

How to free ourselves from the violence of positivity at work? The discussion about emancipation in the work environment is often divided into macro-emancipation, which describes collective movements & organised labour, and micro-emancipation, which refers to:

concrete activities, forms, and techniques that offer themselves not only as means of control, but also as objects and facilitators of resistance and thus, as vehicles for liberation. In this formulation, processes of emancipation are understood to be ‘uncertain, contradictory, ambiguous, and precarious. (Alvesson and Willmott, 1992: 446)

The micro-emancipation concept was created as a critical response to the macro approach. Alvesson and Willmott pointed out that despite all of the victories of organised revolts in the fight with various oppressions, the weak point of macro-emancipation is their elitist character. In response to the macro model where intellectually enlightened individuals or small groups lead the crowd, micro-emancipation proposes a non-leader framework focused on everyday life where everybody can spontaneously seek liberation through small disobedience, sabotage or cynicism.

On the other hand, the authors of ‘Beyond macro- and micro-emancipation: Rethinking emancipation in organization studies’ take a critical look at the micro-emancipation concept. In the paper, they highlight the banality of the framework and a possible trap – the false impression of a rebellious act, when in fact the liberation energy is wasted on unproductive activities. Another fragility is the fact that micro-emancipation can be treated as a safety vault, embraced and, as a result, misused by the management. In the paper, they emphasise unnecessary or even pernicious defragmentation resulting from micro and macro division, which beclouds the complete image of the overall, profound revolt.

Unguilty Pleasures

Through ‘Unguilty Pleasures’ I advocate for the abandonment of the misleading division and embracing Rancière’s understanding of emancipation as a constant renegotiation of common sense through the process of conflict and dissensus. I see this approach as the most valuable and productive in the context of positivity in the modern workplace and the entailed oppression. The project seeks to create a space for this renegotiation – verbalisation of disagreement, resistance towards dominating work dogmas, coping strategies – and embrace the dissensus.

The project is informed by Alvesson and Willmott’s micro-emancipation concept but aims to be seen in the wider context together with other micro and macro-emancipatory activities. Although I appreciate accurate arguments made by Huault, Perret and Spicer (2012), the authors of the mentioned article and their contribution in the discussion of workers’ emancipation, I see the potential and vitality in micro-disobedience at work as an approachable and at the same time effective framework. Despite all the weak points, it would be a waste to overlook the possible benefits resulting from the relatable and inclusive character of those micro-acts. They can be banal, but what is more important, they are universal, and thanks to this they can be easily adapted by each and every one. If the main goal is to disrupt and change the common sense, the wide scope together with the sense of collectiveness built on the realisation that you are not the only one in the subtle but important fight helps to achieve the main goal – renegotiate what does the ‘normal’ mean. The managerial appropriation of micro-emancipation activities is highly probable, but this is the inevitable dynamic – many revolts, in the end, were embraced by the oppressor and despite the success, somehow used against the revolutionary group or following generations. Every concept can be misused and capitalise on becoming a cynical version of it’s initial values, but does it mean that we should abandon any action and stay passive? The revolution neither has a clear beginning nor has a full stop end. Rather it’s a process in constant flux – what was satisfying yesterday devaluates tomorrow. Renegotiation never ends.

What was missed in the critique of micro-emancipation mentioned before is the neoliberal threat of focusing on the individual and putting the responsibility for all actions on the worker themself. ‘Unguilty Pleasures’ does not aim to pressure workers and can’t be treated as an alternative to traditional forms of fighting for workers’ autonomy such as organised labour, collective bargaining or direct actions. But sometimes emancipation starts from micro-disobedience (Alvesson & Willmott, 1992). The project seeks to promote and normalise a critical discussion about the dominant positivity dogma at the workplace and to politicise the micro-disobedience act.

To challenge the dominant, broadly-promoted aesthetic of happiness, we should strive not only to promote its antithesis but to create and embrace a new anti-aesthetic. This process starts with the rejection of the pre-imposed corporate happiness rigour. Instead of this, I want to acknowledge and propose an open dialogue about small, but what is more important, spontaneous misbehaviours – manifestations of joy, free from the managerial corset – Unguilty Pleasures.

Slackers of All Lands Unite

These micro-disobediences can be binge-watching Netflix during work time, taking unnecessarily long breaks, choosing a different route than the algorithm decides, being intentionally mean to your customer or being grumpy when everybody is overenthusiastic or maybe not participating in the corporate socials. My project, Unguilty Pleasures, aims to archive past and gather present examples of these acts of micro-disobedience at work. And through these ‘coming-outs’ create a space free of slack-shaming and overstepping guilt. Because at the end of the day – you felt satisfaction not because you were sticking to the rules, but because you do you.

- Alvesson, M., Willmott, H. (1992) ‘On the Idea of Emancipation in Management and Organization studies’, Academy of Management Review 17(3): 432–64.

- Cabanas, E., & Illouz, E. (2019). Manufacturing Happy Citizens: How The Science and Industry of Happiness Control Our Lives. Polity Press.

- Cederström, C. (2019). The happiness fantasy. Polity Press.

- Davies, W. (2016). The Happiness Industry: How the Government and Big Business Sold us Well-being. Verso.

- Edwards, R. (1985). Contested Terrain. Basic Books.

- Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? O Books.

- Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit jobs. Simon & Schuster.

- Han, B., & Butler, E. (2017). Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. Verso.

- Han, B., & Butler, E. (2015). The Burnout Society. Stanford Briefs, an imprint of Stanford University Press.

- Haybron, D. (2020, May 28). Happiness. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/happiness/

- Huault, I., Perret, V., & Spicer, A. (2012). Beyond macro- and micro- emancipation: Rethinking emancipation in organization studies. Organization, 21(1), 22-49. doi:10.1177/1350508412461292

- Umoh, R. (2018, May 21). Why Amazon pays employees $5,000 to quit. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/21/why-amazon-pays-employees-5000-to-quit.html

![Twitter post by [BBCNews]](https://unguiltypleasures.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/wristband-copy.png)

![Reddit post by user [u/Xineasaurus] posted in [r/ABoringDystopia]](https://unguiltypleasures.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/no7n0vz3eg821.jpg)